Although I scan all my negatives so that I can share photos online, I prefer to make prints in the darkroom. I find it to be an engaging technical craft that provides endless things to learn.

Recently, thanks to a few YouTube videos, I learned about f-stop printing and the technique’s biggest champion, Gene Nocon. It didn’t pique my interest enough to spend over $700 on the timer that the videos were plugging, but enough that I grabbed a copy of Gene Nocon’s book Photographic Printing via a inter-library loan.

What is F-stop printing?

The basic idea of f-stop printing is to control your print exposure the same way you control the exposure of the original negative. When taking a photo I can double the light by opening my lens a stop or by doubling my exposure time. Or I can halve the light by doing the opposite. If a whole stop is too much I can fine tune things by adjusting by a partial stop.

Frequently in the darkroom we ignore this approach of doubling and halving light, instead choosing to increase exposure by a set amount of time (usually 5 seconds). While going from 5 to 10 seconds does double the amount of light, going from 10 to 15 only increases the light 1.5 times. This lack of consistent halving & doubling can make it hard to a create print at a new size, with new paper, or on a new enlarger.

Compared to the usual darkroom approach, f-stop printing lets you make your print the same way you made your negative — by halving and doubling the light. As a result print making is easier and more consistent, even when paper, enlargers, etc. change.

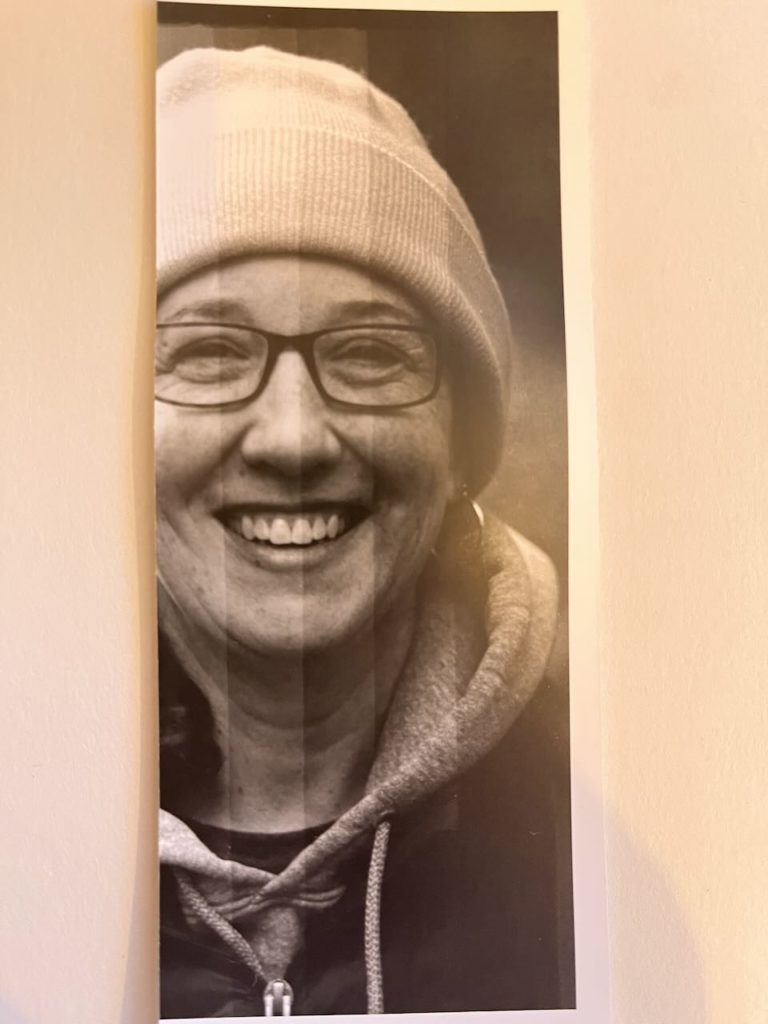

An illustrated example should make this clearer. I wanted to do a print of this photo:

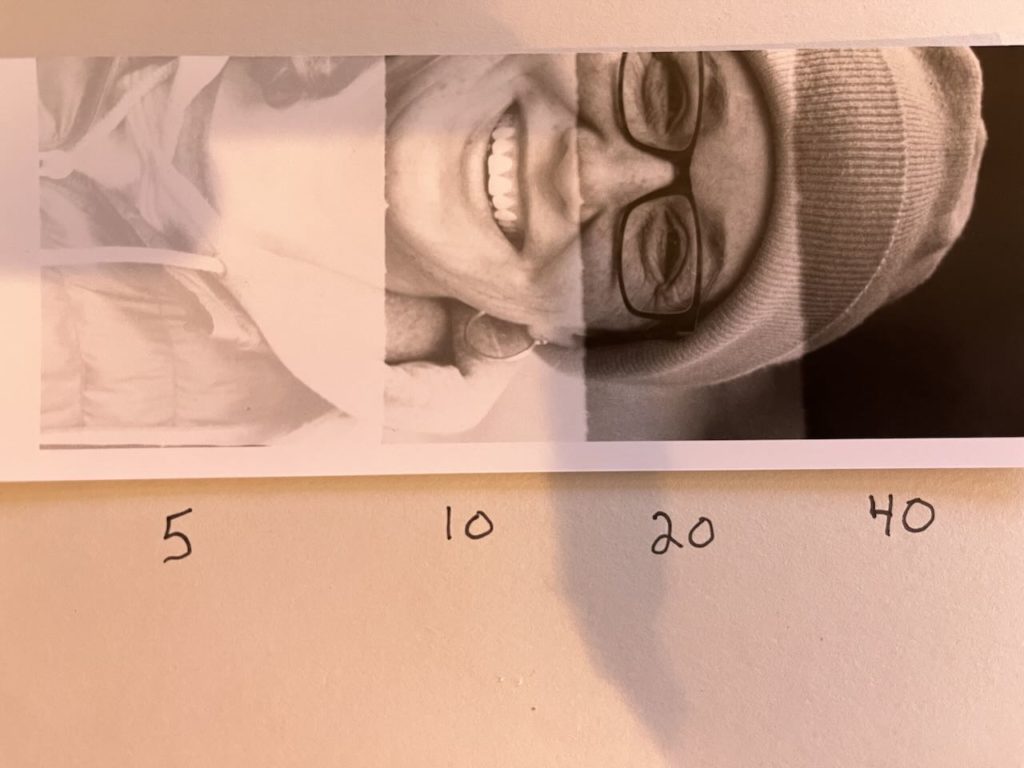

To make a basic test strip I used doubling amounts of light by doubling my exposure time: 5/10/20/40 seconds. Specifically:

- Expose the entire paper for 5 seconds

- Cover one 1/4 of the paper and expose for 5 seconds

- Cover 1/2 of the paper and expose for 10 seconds

- Cover 3/4 of the paper and expose for 20 seconds

The 20 second exposure seems fine for my base time (it looks too dark online, I realize. It looks better in person). But her hat is too light at 20 and too dark at 40.

You’ll frequently find that the correct exposure lies between two of the full stops. In which case you can adjust by using partial stops, just as you would do with your camera. Nocon provides a table of 1/4 stop timings. A sample of which looks like:

| Full Stop | 5 | 10 | 20 | 40 | 80 |

| +1/4 | 5.9 | 11.9 | 23.8 | 47.6 | 95.2 |

| +1/2 | 7.1 | 14.1 | 28.3 | 56.6 | 113.2 |

| +3/4 | 8.4 | 16.8 | 33.6 | 67.3 | 134.6 |

So I made another test strip of 1/4 stops between 20 and 40 seconds.

Back to that $700 darkroom timer for a minute. The nice thing about it (and other f-stop timers like it) is that they have all these timings programmed in. So I could set the timer to start at 20 seconds and then have it increase by 1/4 stop for each strip with a simple push of a button.

But you can do f-stop printing without a fancy timer. I wanted to see all the quarter stops between 20 and 40 so I:

- Exposed the entire paper for 20 seconds

- Covered 1/5 and exposed for 3.8 seconds (bringing the second strip up to 23.8)

- Covered 2/5 and exposed for 4.5 seconds (bringing the third strip up to 28.3)

- Covered 3/5 and exposed for 5.3 seconds (bringing the fourth strip up to (33.6)

- Covered 4/5 and exposed for 6.4 seconds (bringing the final strip up to 40)

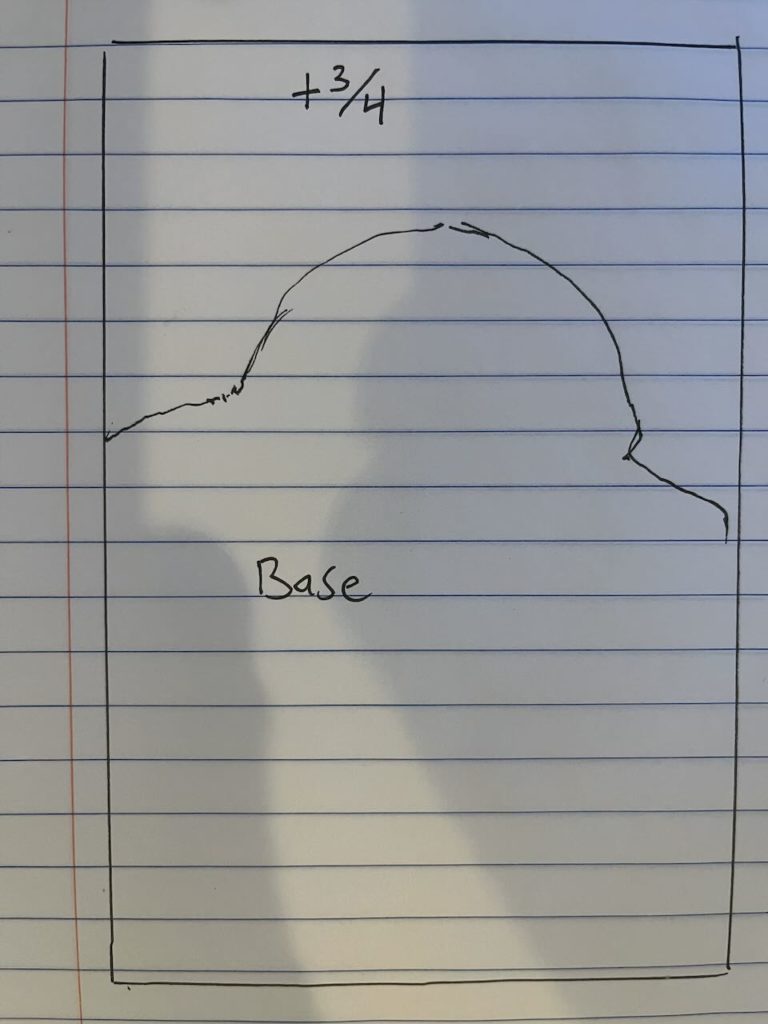

Based on this I decide to burn in the hat and background 3/4 of a stop over my base exposure.

Not going to lie, that is a bit fiddly. Which is why people make f-stop timers.

Why Those Numbers?

A question that I had before reading this book is why are the times so odd? Shouldn’t they look like this?

| Full Stop | 5 | 10 |

| +1/4 | 6.25 | 12.5 |

| +1/2 | 7.5 | 15 |

| +3/4 | 8.75 | 17.5 |

After all, the math makes sense. 10 is double 5. 15 is double 7.5. Etc. In the technical-heavy final chapter to his book Nocon explains his numbers. I won’t reproduce the entire thing here but it has to do with him starting at a 1 second base exposure and doubling from there: 1, 2, 4, 8, 16. These are all exponents of 2 (i.e., 1 is 20, 2 is 21, and 4 is 22). From there he does quarter stops (i.e. 21.25). The resulting numbers are too small to be useful enlarger exposure times so he then multiplies the whole thing by 5. He wraps up his explanation with the delightful sentence

I have already explained why arbitrary values of time prove to be confusing.

Gene Nocon, Photographic Printing

Advantages of F-stop Printing

Considering the fiddly (or expensive) aspects of f-stop printing, why would you do it? It makes reproduction across different enlargers/papers/sizes a lot easier and consistent, saving both time and money.

Here’s the printing map for my photo

My tests show that most of the print looks fine at my base exposure. One section needs to be burned in for 3/4 of a stop. Now, when I want to make a new size of the photo I just need to determine that base exposure and I’ll know exactly how long to burn and dodge.

For example: if my base exposure for a 5×7 print is 14.1 seconds then I know that my burn-in section needs 23.8 seconds of light (3/4 of a stop over 14.1).

When I change the enlarger height for a new paper size I might find that my new base exposure is now 33.6 seconds. But my burn-in section is still 3/4 of a stop higher. So I know that my burn-in gets 55.6 seconds. No need to do more test strips. Neat!

If you use a light meter in the dark room you can easily determine your new base exposure by taking a light reading with the original enlarger height and a reading with the new enlarger height. That will tell you how many stops of light you’ve lost and you can adjust your base exposure accordingly. Or you can make a new test strip and dial it in that way.

Learning More and Wrap Up

Gene Nocon explains all of this better than I do. There’s a video of him discussing the approach on YouTube. And if you’re able to find a copy of his book I recommend it. It’s full of helpful tips, even if you’re not interested in f-stop printing. Nocon was an engaging, down-to-earth, and economical writer.

The book Way Beyond Monochrome also discusses f-stop printing and provides tools to control your exposure in 1/6th of a stop increments. They also provide a tool to convert a common GraLab-style timer to f-stop printing. This book is easier to find than Nocon’s and covers a ton more subjects, but I found Nocon’s work easier to read and enjoy.

Thanks for reading! You can always keep up to date by adding the site to a RSS reader or follow me over on Mastadon at https://mastodon.art/@ianwhitney. You can also subscribe for email notifications.

Leave a Reply